Certain social dynamics can negatively impact concussion recovery (7/24/25 Newsletter)

In this newsletter: Correction, Concussion Alliance Lunch & Learn, Opportunities, Education, Sports, CTE & Neurodegeneration Issues

Writers: John Lin, Anni Yurcisin, & Sam Chen

Editors: Conor Gormally & Malayka Gormally

Do you find the Concussion Update helpful? If so, forward this to a friend and suggest they subscribe.

Correction

We’d like to offer a correction on last week’s synopsis in our Self-Care category: Common pain relievers show promise in speeding concussion recovery. The synopsis mistakenly stated that acetaminophen is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) when it’s not.

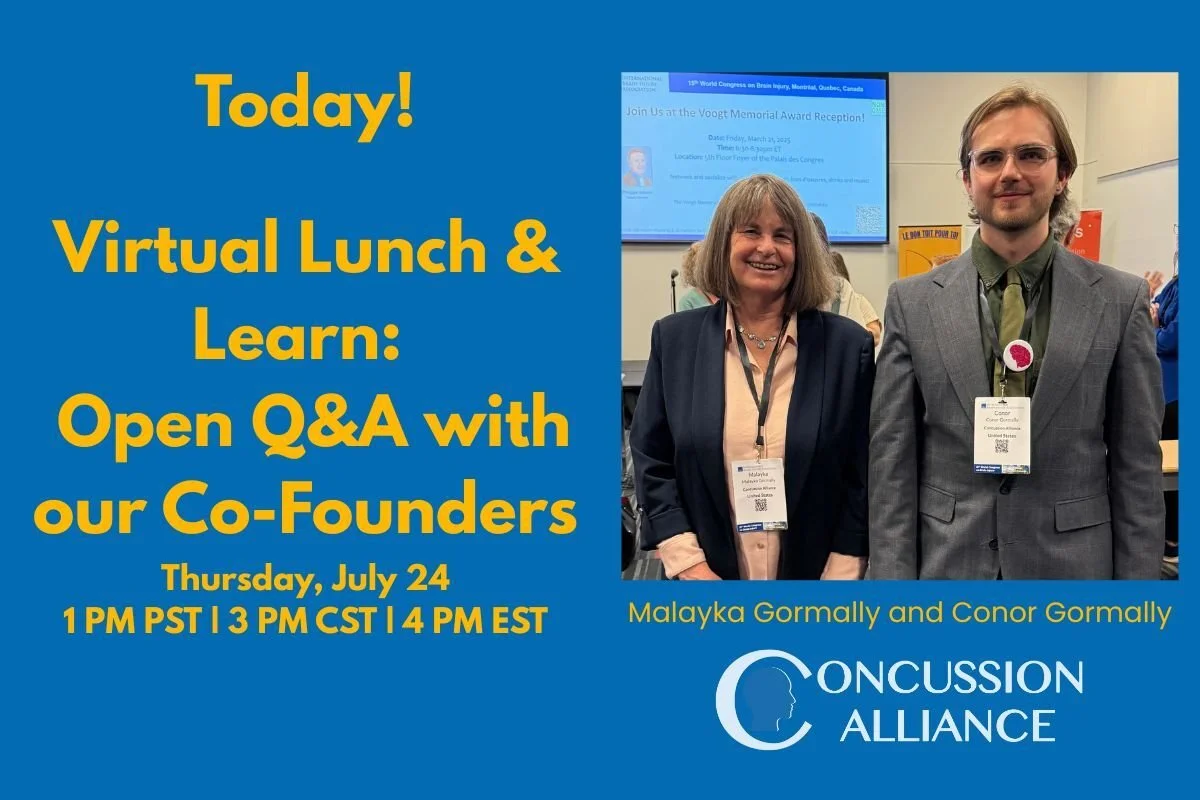

Summer Concussion Alliance Lunch & Learn - Today!

July 24: Join Concussion Alliance Co-Founders for an Open Q&A at 1 PM PDT, 3 PM CDT, 4 PM EDT

On July 24th at 1 PM PDT | 3 PM CDT | 4 EDT, join Concussion Alliance Co-Founders Conor Gormally & Malayka Gormally for our second virtual Lunch & Learn webinar! This Lunch & Learn will be an open Q&A with Conor and Malayka, so bring on your concussion questions!

Note: We are unable to answer any personal questions about an individual’s specific medical issues, and these answers do not constitute medical advice.

Opportunities

Wednesday, August 13, 6 pm EDT: A webinar, Getting Things to Stick: Strengthening Memory and Habits after Brain Injury, presented by Stephanie Wagner, Director of Learning & Development at Healthy Minds Innovations, and hosted by the nonprofit LoveYourBrain. Register in advance: there is a sliding scale fee starting at free.

Education

Certain social dynamics can negatively impact concussion recovery

A qualitative study by Bernadette A. D'Alonzo et al. explored how social and cultural dynamics surrounding expectations of recovery affected concussion recovery among a cohort of Division 1 collegiate student-athletes. For the study, published in The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, the researchers interviewed a sample of 22 collegiate athletes about how the pressures of expectations, emotions, and returning to school/athletics impacted their concussion recovery. These insights from collegiate athletes illustrate the variability and pressures in the recovery process of concussions; factors such as frustration in not being able to participate and pressures of returning to "normal" were prominent in the student-athletes. This study illustrates the importance of integrating and streamlining return-to-play and return-to-academics strategies, as well as improving support programs that encourage social engagement, which is essential to concussion recovery. The authors also recommend establishing peer-to-peer support groups for injured athletes.

The study authors interviewed 22 collegiate student-athletes (from 15 different sports teams) who had sustained at least one sports-related concussion (within one year of the start of the study) and who "progressed through the return-to-play protocol." D'Alonzo et al investigated four "key phases" of their experience with concussion recovery: immediately post-diagnosis, during recovery, decision-making about returning to sport and academics, and returning to sport and academics. In the post-diagnosis phase, the authors found that athletes' comparisons to their peers' attitudes and expectations of recovery "shaped their attitude towards care-seeking, symptom severity…and expectations for speed of recovery." In the recovery phase, some of the athletes inaccurately believed that strict rest in a dark room ("cocooning") helped recovery.

Most athletes found that the "recovery process was not smooth," with some finding their coordinated care by doctors and trainers helpful and others finding that "the care was too hands off, passive, and disorganized". Some students felt a lack of control over their decision-making regarding return to sport and academics. Some felt that they were "stuck in one recovery phase," and others expressed frustration that decisions about return to school and sport were out of their control–– and felt like their care team or coach was holding them back. Many expressed anxiety about "falling behind" in their academics and "prioritized minimizing missed classes".

In the final phase of returning to sport and academics, the authors noted that participants often reported lingering symptoms throughout their gradual return to sport/academics. Despite these lingering symptoms, they expressed difficulty in finding support for managing their symptoms. Symptoms such as trouble focusing and headaches continued to cause academic problems. Some athletes "felt they were not given enough support academically" and acknowledged that the timing of the injury was a significant factor. While some were able to attend virtual lectures online or work during an academic break, many athletes were affected by an injury that interfered with exam season. Some athletes noted that weak communication between athletic and academic departments made the burden of asking for support fall on them "when their symptoms were most intense." One athlete discussed responsibility and recommended if, "the athletic department on behalf of the school can email your professors for you and at least just let them know like, hey, this student has suffered a concussion."

The authors found that social engagement with family and friends for reassurance was crucial in recovery, whereas social isolation and a lack of understanding from others led to difficulties with mental health for many. Those who were able to communicate with family, friends, and teammates were able to seek support and reassurance about their concussion, which helped them make better-informed decisions. On the other hand, athletes who were unable to engage socially with family or were not able to attend events reported "exacerbated feelings of loneliness throughout recovery".

Sports

Football Australia’s new concussion guidelines and 8-step return-to-play

In response to growing public health concerns surrounding sports-related concussion (SRC) in football — known as soccer in the United States — Football Australia, the governing body of football in Australia and a member of FIFA, has released new Community Sports-Related Concussion Guidelines. The Community Sports-Related Concussion Guidelines acknowledge the important public health concerns related to SRC, affecting football players of all ages, genders, and levels of the sport. These community guidelines and Graded Return to Play Program (Adult and Youth versions) provide information and recommendations to assist in the management of SRC among community football participants, including club (amateur) players, semi-professional and non-elite participants, and club and competition administrators. While acknowledging the inherent risks of contact sports, the guidelines aim to reduce the risks associated with SRC through timely diagnosis, evidence-based management, and structured return-to-play procedures to ensure the safety and protection of all players.

Concussion Alliance is concerned that the community guidelines state, “The majority of adult SRC’s resolve in a short period of time (7-10 days),” followed by a citation to the Australian Concussion Guidelines for Youth and Community Sport, which does not say anything about a 7-10 day resolution of SRC. For context, the 6th Consensus Statement on Concussion in Sport, referenced in these guidelines, states that for all ages, SRC typically resolves in 1 month. We are also concerned that the community guidelines and graded return-to-play programs do not require medical clearance before returning to full-contact training, which is a feature of the Australian Concussion Guidelines for Youth and Sport and the 6th Consensus.

The guidelines offer a Child and Adolescent Graded Return to Play Program and an Adult Graded Return to Play Program, which integrate cognitive tasks alongside physical milestones. The guideline provides a more detailed and comprehensive approach compared to the CDC’s 6-Step Return-to-Play Progression, which, unlike the Australian guidelines, does not include a fixed 21-day recovery period or similarly structured return-to-school protocols. The 8-step progression is: relative rest & recovery, resume daily living activities, light exercise & cognitive work, moderate exercise & cognitive work, running and sport-specific drills & increase cognitive work, sport-specific training without contact & normal cognitive work, resume full-contact training, and return to competition.

These guidelines were developed in collaboration with the Australian Federal Government and reflect Football Australia’s broader commitment to increasing community education and awareness about concussion. The Community Sports Concussion Guidelines aim to educate individuals about the importance of timely diagnosis, evidence-based recovery protocols, and safe return-to-play procedures to better protect athletes.

CTE & Neurodegeneration Issues

Two studies evaluate neurodegeneration risk in mid-life former rugby players

Two studies have recently examined the effects of repetitive head impacts and traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) in retired elite-level rugby players at midlife. Neil S. N. Graham et al. published a study in Brain that investigated blood and neuroimaging biomarkers in retired elite rugby players that could indicate an increased risk of neurodegenerative disease in the future. They found an increase in p-tau217, a form of the tau protein associated with neurodegenerative disease. Thomas D Parker et al. published a study in Brain that looked at clinical cognitive dysfunction, self-reported symptoms, and MRI imaging to examine the effects of repetitive head impacts and concussions in retired elite rugby players. While the retired players reported higher depressive and anxiety symptoms and more burdensome concussion symptoms, they didn't score significantly lower on cognitive tests than non-rugby players; however, some players had brain abnormalities found with imaging. Taken together, these studies suggest that in the context of an elite-level rugby career, repetitive head impacts and TBIs, including multiple concussions, contribute to poor quality of life (particularly with mood), and appear to increase the risk for long-term neurodegenerative disease, with evidence for biomarkers aiding "in the evaluation of long-term effects of sports head impact exposure."

Graham et al. studied a group of mid-life 200 ex-rugby players who experienced significant TBIs throughout their careers and 33 unexposed control subjects. The authors utilized blood and neuroimaging biomarkers associated with long-term neurodegenerative diseases like Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) and Alzheimer's, relating the biomarker data to the clinical phenotypes of various neurodegenerative diseases, like CTE. The clinical phenotype of CTE—the observable characteristics of an individual with a condition—has been termed "traumatic encephalopathy syndrome" (TES). TES was more common in the retired players who had elevated p-tau217: retired players with elevated levels of p-tau217 were 2.8 times more likely to fulfill criteria for TES than retired players with non-elevated levels. The retired players, on average, had p-tau217 concentrations that were 17.6% higher than those of controls. The authors also tested for the blood biomarker NfL and found that retired players with higher NfL had more prevalent depressive and anxiety symptoms.

Parker et al.'s study used self-report symptom questionnaires, cognitive testing, TES classification, and MRIs to examine the impact of repetitive head impacts and concussions on a group of 200 mid-life, former elite rugby players who were experiencing negative cognitive symptoms. The former players were divided into a "high concussion" group (a history of 8 or more concussions) and a "low concussion" group (a history of 7 or fewer concussions). Overall, the former players had worse quality of life scores, higher pain symptom scores, higher depressive and anxiety symptoms, higher burden of post-concussion symptoms, and higher self-reported behavior rating of executive dysfunction compared to a cohort of 33 matched healthy control subjects. Additionally, 28.5% and 35.2% of the former players had abnormally high levels of self-reported depressive and anxiety symptoms, respectively; the" high concussion group" had even higher levels: 38.9% and 42.2%, respectively. Despite the self-report findings, former players didn't show statistically significant differences in neurocognitive testing compared to the control group. However, 12% of former players also met the criteria for TES.

Further research is needed to confirm both the pathological significance of elevated p-tau217 and the link between repetitive head impact and TBIs with TES and other neurodegenerative diseases. However, these studies illustrate the importance of both using biomarkers to evaluate the long-term effects of sports TBI exposure and listening to the experiences of individuals with sports TBI exposure.

You Can Support Concussion Patients

Join our community of monthly donors committed to improving how concussions are prevented, managed, and treated, thereby supporting long-term brain health for all. Learn more.

You can also make an impact with a one-time gift or tax-friendly options such as Donor Advised Funds (DAFs), IRA Charitable Rollovers, and Planned Giving: leave a gift in your will. Learn more.